- Published on

Bounded contexts: from compile-time hierarchies to runtime composition

- Authors

- Name

- Damian Płaza

- @raimeyuu

How can we help?

Meet Tom (you might recall him from Many Faces of DDD Aggregates in F#).

As a successful businessman, after he earned tons of money with disco clubs, gamedev and now he tries his luck in software for public speaking.

Hi, my name is Tom.

Can you help me with some ideas?

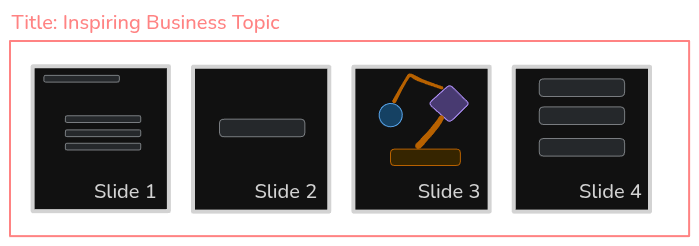

Tom showed us a rough sketch of his idea, in the form of low-fidelity wireframe:

A slide deck, consisting of multiple, ordered slides, each slide having some content (and of course notes for the speaker, we know it even though Tom forgot to draw it).

Let's present some ideas

Sounds like an interesting problem to tackle, right?

If you were able to listen carefully, dear Reader, you might have captured some important concepts Tom mentioned.

Let's try to represent them using the code, firstly starting with the main, domain concept - a slide deck.

There are also slides, each having some content, notes and ordering within the deck.

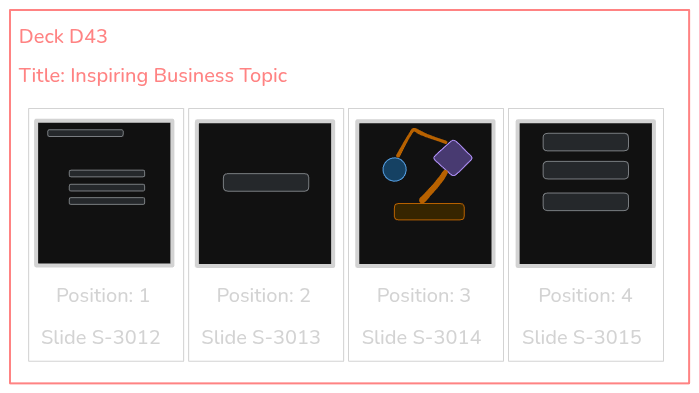

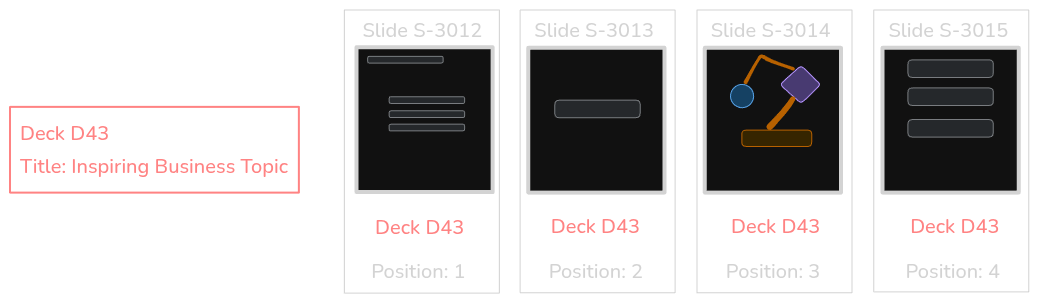

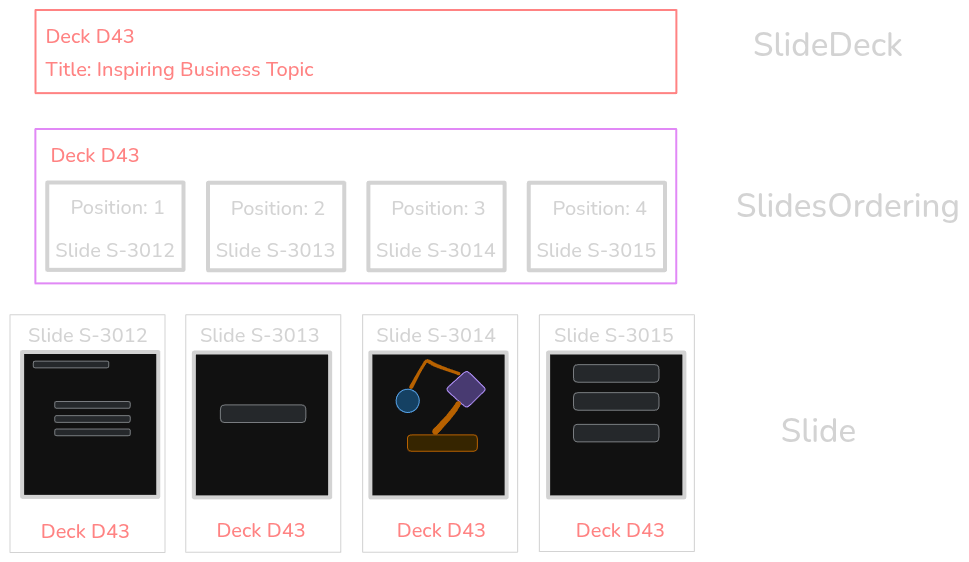

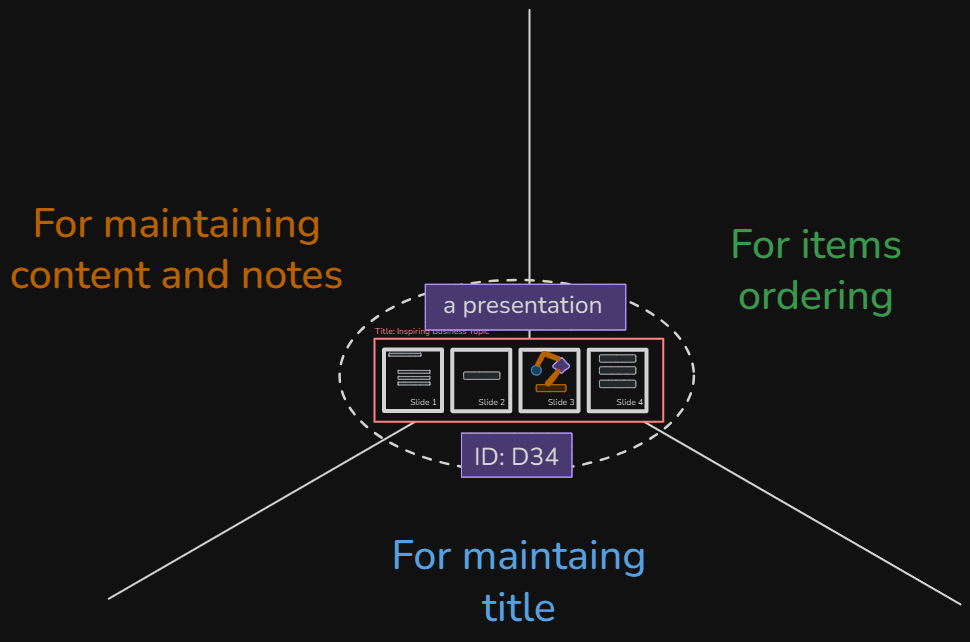

Here is how we can sketch it on the whiteboard:

An avid reader might notice that a slide deck available under identifier "D43" has many slides, and has title "Inspiring Business Topic".

Each slide has its own identifier (e.g. "S-3012") and position within the deck (e.g. 1) and unique content, for instance, consisting of text only.

We can start by defining a SlideDeck class:

class SlideDeck {

// data goes here

}

Many times we've heard that focusing on nouns might lead us to build bags-of-data, rather than rich domain models.

What behaviours can we add to our SlideDeck class?

class SlideDeck {

deckId: DeckId;

title: Title;

slides: Slide[];

addSlide(): { slideId: SlideId, position: PositiveInt } {

// ...

},

deleteSlide(slideId: SlideId): void {

// ...

}

duplicateSlide(slideId: SlideId): { newSlideId: SlideId, position: PositiveInt } {

// ...

}

moveSlide(slideId: SlideId, newPosition: PositiveInt): void {

// ...

}

moveSlides(slideIds: SlideId[], newPosition: PositiveInt): void {

// ...

}

updateContent(slideId: SlideId, content: Content): void {

// ...

}

updateNotes(slideId: SlideId, notes: Notes): void {

// ...

}

}

Self-describing set of capabilities that are provided by our rich domain model - SlideDeck.

Now, we can imagine that such model can be applied in a such a way:

type NewSlideDeckContext = {

slideDeckRepository: ForCreatingSlideDecks,

uuid: ForGeneratingUuids

}

export const newSlideDeck = (context: NewSlideDeckContext) => async (): Promise<DeckId> => {

const deckId = context.uuid.new()

const slideDeck = await context.slideDeckRepository.create({ deckId })

return deckId

}

type AddSlideContext = {

slideDeckRepository: ForLoadingSlideDecks & ForSavingSlideDecks,

uuid: ForGeneratingUuids

}

export const addSlide = (context: AddSlideContext) => async (deckId: DeckId): Promise<{ slideId: SlideId, position: PositiveInt }> => {

const slideDeck = await context.slideDeckRepository.load(deckId)

const { slideId, position } = slideDeck.newSlide()

await context.slideDeckRepository.save(slideDeck)

return { slideId, position }

}

type MoveSlideContext = {

slideDeckRepository: ForLoadingSlideDecks & ForSavingSlideDecks

}

export const moveSlide = (context: MoveSlideContext) => async (deckId: DeckId, slideId: SlideId, newPosition: PositiveInt): Promise<void> => {

const slideDeck = await context.slideDeckRepository.load(deckId)

slideDeck.moveSlide(slideId, newPosition)

await context.slideDeckRepository.save(slideDeck)

}

// ... and so on for other use cases

One can now visualize that those functions (or commands, if you will), will be utilized in HTTP handlers or message handlers, depending on the needs.

We could say that for the sake of simplicity, those operations will be exposed as HTTP endpoints, e.g.:

POST /slide-decks-> creates a new slide deckPOST /slide-decks/{deckId}/slides-> adds a new slide to the deckPATCH /slide-decks/{deckId}/slides/{slideId}/move-> moves the slide to a new position

Presenting problems

Well, everything was going well until Tom came back with some "additional requirements".

Turned out that all worked fine, but there were some unspoken needs.

The application really helps getting work done.

I am adding many notes so one of my assistants does the content polishing - I want to save my precious time.

I can't move on, as an assistant changes the content, or the other way round.

Can we do something about it?

Initially, we only explored user interface, so the consequence that an end user sees - which is merely a snapshot of the state - we didn't ask important questions about what is the workflow, what are the rules and constraints.

Seems like a typical concurrency problem.

Optimistic control for the rescue!

We can add a version property to our SlideDeck class, and bump it whenever we save the changes.

When loading the slide deck for modification, we also load the version.

When saving, we check if the version hasn't changed in the meantime.

Easy!

But user experience might be a bit clunky - users will have to reload the slide deck and re-apply their changes.

Or maybe...We could work on the model level?

Rethinking a solution #1

If changing the title is independent from reordering slides, maybe we could isolate that responsibility?

We would then create a new solution.

We could potentially rethink our problem and organize behaviors around smaller pieces of the slide deck - Slides.

Let's try to perform further decomposition and treat each slide as a consistency unit, enabling concurrent modifications of different slides within the same deck.

So now, it's not a SlideDeck that has all the behaviors, but rather each Slide has its own behaviors, and stop being a mere data structure.

A SlideDeck keeps track of its title and each Slide keep track of its content, notes and position within the deck.

class Slide {

slideId: SlideId;

deckId: DeckId;

position: PositiveInt;

content: Content;

notes: Notes;

updateContent(content: Content): void {

// ...

}

updateNotes(notes: Notes): void {

// ...

}

moveTo(newPosition: PositiveInt): void {

// ...

}

duplicate(): Slide {

// ...

}

}

This new model establishes the collision boundary per slide, rather than per deck.

Now, two users can concurrently modify different slides, and their contents, within the same deck without stepping on each other's toes.

Let's examine updating a content of a single slide:

type UpdateSlideContentContext = {

slidesRepository: ForLoadingSlide & ForSavingSlide

}

export const updateSlideContent = (context: UpdateSlideContentContext) => async (deck: DeckId, slideId: SlideId, newContent: Content) => {

const slide = await context.slidesRepository.getBy({ deck, slideId })

slide.updateContent(newContent)

await context.slidesRepository.save(slide)

}

Same goes for reordering slides...Right?

Hm, not quite.

Earlier, we had operations like moveSlide(slideId: SlideId, newPosition: PositiveInt) and moveSlides(slideIds: SlideId[], newPosition: PositiveInt) on the SlideDeck, but now each Slide can only move itself.

A SlideDeck model was responsible for ensuring, that after moving a slide or slides, everything is consistent.

The logic itself might have been non-trivial, as it required not only taking care of slides being a subject of reordering, but also other ones that are affected by such action.

Let's see how previous model - based on SlideDeck - could satisfy a capability for moving a single slide:

// 👇 public method in `SlideDeck`

moveSlide(slideId: SlideId, newPosition: PositiveInt) {

const slideIndex = this.slides.findIndex(s => s.slideId === slideId);

if (slideIndex === -1) {

throw new Error(`Slide ${slideId} not found in deck`);

}

const currentPosition = this.slides[slideIndex].position;

if (currentPosition === newPosition) {

return;

}

if (newPosition < currentPosition) {

moveAffectedSlidesUp({ newPosition, currentPosition }) // 👈 private method in `SlideDeck`

} else {

moveAffectedSlidesDown({ newPosition, currentPosition }) // 👈 private method in `SlideDeck`

}

this.slides[slideIndex].position = newPosition;

this.slides.sort((a, b) => a.position - b.position);

}

SlideDeck's private methods moveAffectedSlidesUp and moveAffectedSlidesDown methods take care of other slides and update their position, accordingly.

Here we can see that our previous model needed to make some decisions to keep consistency.

Now, we organized responsibilities differently, which does not mean that this logic (knowledge application, "ifs") disappeared.

As someone said: "complexity does not disappear, it gets moved".

Each Slide is responsible for moving itself, so where would we locate the logic for coordinating multiple Slides?

One of the possible solutions, given a new Slide-based model we selected, would be:

type MoveSlideContext = {

slidesRepository: ForLoadingsManySlides & ForSavingManySlides

}

// 👇 public function int he module scope

const moveSlide = (context: MoveSlideContext) => async (deck: DeckId, slideId: SlideId, newPosition: PositiveInt) => {

const allSlides = await context.slidesRepository.loadAllIn({ deck })

const slideToMove = allSlides.find(slide => slide.Id === slideId)

if(!slideToMove)

throw new Error(`Slide ${slideId} not found in deck ${deck}`)

if(slideToMove.position === newPosition)

return;

if(slideToMove.position < newPosition) {

moveAffectedSlidesDown({ // 👈 private function in the module scope

allSlides,

newPosition,

currentPosition: slideToMove.position

})

} else {

moveAffectedSlidesUp({ // 👈 private function in the module scope

allSlides,

newPosition,

currentPosition: slideToMove.position

})

}

slideToMove.moveTo(newPosition) // 👈 public method in `Slide`

await context.slidesRepository.saveMany(slidesToUpdate);

}

In a way, many things changed, but nothing really changed - except we moved the logic between different levels.

Maybe we were able to isolate updating contents of two different slides, but reordering still isn't free from "stepping on each other toes".

What's more, we haven't explored "duplicating slide" capability which probably involves duplicating contents of a slide and doing the work on reordering level.

So that action isn't free from "stepping on each other toes" too.

Moving a single slide involves other slides: their positions and contents too.

This again, does not feel right, isn't it?

Of course, we could still bet on delegating that to infrastructure level and use optimistic concurrency with retries, but under the skin it feels there's something more.

Should we again work on the model level?

Rethinking a solution #2

If changing the title is independent from reordering slides, maybe we could isolate that responsibility?

We would then create yet another solution.

In some scenarios, a single Slide model was doing great - especially when it came to updating its contents (and possibly with speaker notes too).

But that model wasn't enough when we explored operations spanning multiple Slides - like reordering.

Related logic (knowledge, "ifs") manifested itself in "the application level", where commands/queries (or application services) live typically.

An avid designer might take this "problem" as a diagnostic signal, a symptom.

Complexity does not disappear, it gets moved.

We could use anti-requirements heuristic and check the rules - if there are any of these that require both slide position and its content, at the same time.

For example: how probable is it that we wouldn't be able to move a slide if it contains, e.g. five rectangles?

Or another case, what about the rule: "only slides having images with size lower than 5MB can be moved"?

It sounds silly, isn't it?

Yet another diagnostic signal to incorporate in our designing process.

Should we reorganize responsibilities differently, again?

If reordering was "a weak point" of single Slide, maybe a SlideDeck will be a good fit for it?

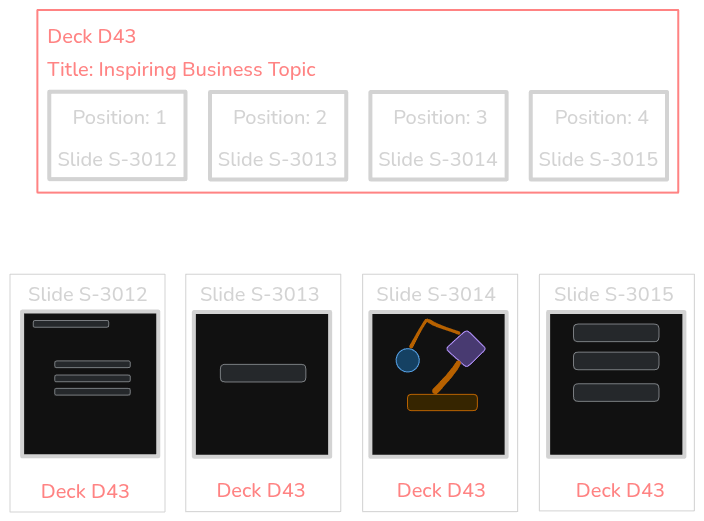

In this design, a Slide knows to which deck it belongs to and what its contents are (along with related speaker notes).

Contrary to that, a SlideDeck knows its title and what is the correct ordering (represented by a position, e.g. 1) of each slide (represented as slide identifier, e.g. "S-3012").

Now, a Slide got a little slimmer:

class Slide {

slideId: SlideId;

deckId: DeckId;

content: Content;

notes: Notes;

updateContent(content: Content): void {

// ...

}

updateNotes(notes: Notes): void {

// ...

}

duplicate(): { notes: Notes, content: Content } { // 👈 we're duplicating only contents and notes

// ...

}

}

There's no knowledge about its position. Shall we check SlideDeck?

class SlideDeck {

deckId: DeckId;

title: Title;

slidePositions: { slideId: SlideId, position: PositiveInt }[];

appendSlide(slideId: SlideId): { position: PositiveInt } { // 👈 we renamed "addSlide" to "appendSlide"

// ...

},

deleteSlide(slideId: SlideId): void {

// ...

}

insertSlide(slideId: SlideId, position: PositiveInt): void { // 👈 a new method

// ...

}

moveSlide(slideId: SlideId, newPosition: PositiveInt): void {

// ...

}

moveSlides(slideIds: SlideId[], newPosition: PositiveInt): void {

// ...

}

updateTitle(newTitle: Title) {

// ...

}

}

In this configuration, SlideDeck knows how to reorder slides, based on the needs.

Also, there's no collision when it comes to modifying slide's content and move it in the deck, at the same time - in complete isolation.

An avid reader might notice that all operations we saw and examined so far, are related to changing the state of the system.

Moving a slide, updating its contents, changing slide deck's title, etc. - all of these aim at state change.

Both Slide and SlideDeck are responsible to make decisions, based on the responsibilities we assigned to each of them.

Strange bug

Imagine we deployed the new model (or rather - models, because there are two), which made Tom and his crew amazed.

There were no "stepping on each other toes", Tom could employ his creative workflow and his assitants were putting required details.

When he felt that some slides were fitting elswhere, in the narrative, he just moved them, trusting that the system does its job to ensure the consistency.

Everything worked smoothly, until one day...

...When he decided to rename his presentation title from "Inspiring Business Topic" to "Inspiring Business Topic - 2025 Edition".

But the operation failed saying something like "Cannot change the title", giving the option to retry.

Tom did so, but because he's a curious being, he decided to ask his assistant if he changed something.

"Hmmm, at that time I moved 7 slides related to estimations after team topologies part, as you wished" - the assitant replied.

Tom was puzzled.

He brought those concerns to us, and we can start tinkering around the problem.

Strange.

Tom and his assistant changed the title and reordered slides, at the same time.

Hmm, we've never asked Tom whether changing the title has any constraints related to slide ordering.

The best way to remove assumptions is to collaborate with people, directly.

Imagine that we called Tom and asked an anti-requirement question: Should we make a rule that whenever a title is longer than 40 characters we cannot move slides?

That would be silly, right?

I don't see any reason for that.

Can we fix it, please?

Well, that's a clear answer!

It seems we need to rethink our model(s) again.

Rethinking a solution #3

If changing the title is independent from reordering slides, maybe we could isolate that responsibility?

We would then create a new model - third one.

New organization of responsibilities yields very interesting qualities - with this design, Tom can change the title of the slide deck, while his assistant can reorder slides, at the same time.

We explicitly represented the knowledge about slides ordering in its own model.

Such model was not explicitly communicated through conversations, but rather emerged from observing our struggles (or rather previous models struggles).

It was "living" there implicitly, until we found out that it truly makes sense to manifest it explicitly.

class SlidesOrdering {

deckId: DeckId;

slidePositions: { slideId: SlideId, position: PositiveInt }[];

appendSlide(slideId: SlideId): { position: PositiveInt } {

// ...

},

deleteSlide(slideId: SlideId): void {

// ...

}

insertSlide(slideId: SlideId, position: PositiveInt): void { // 👈 a new method

// ...

}

moveSlide(slideId: SlideId, newPosition: PositiveInt): void {

// ...

}

moveSlides(slideIds: SlideId[], newPosition: PositiveInt): void {

// ...

}

}

SlidesOrdering provides capabilities related to managing slides positions within the deck, whereas SlideDeck is now only responsible for its identity and title.

Slides remain unchanged - each of them keep track of its contents and notes.

Those models are isolated enough to allow concurrent modifications without "stepping on each other's toes".

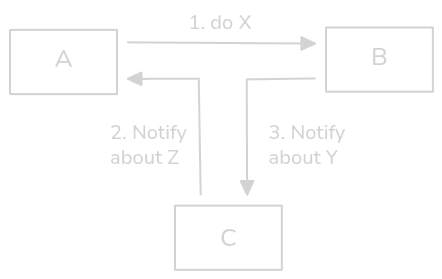

Although there is one capability of the system that now spans multiple models - duplicating a slide.

When duplicating a slide, we need to duplicate its contents and notes (handled by Slide), and also insert a new slide in the ordering (handled by SlidesOrdering).

This is the moment when we are composing their capabilities in runtime:

type DuplicateSlideContext = {

slidesRepository: ForLoadingSlide & ForSavingSlide,

slidesOrderingRepository: ForLoadingSlidesOrdering & ForSavingSlidesOrdering,

uuid: ForGeneratingUuids

}

export const duplicateSlide = (context: DuplicateSlideContext) => async (deckId: DeckId, slideId: SlideId): Promise<{ newSlideId: SlideId, position: PositiveInt }> => {

const slide = await context.slidesRepository.getBy({ deckId, slideId })

const slidesOrdering = await context.slidesOrderingRepository.load(deckId)

const { notes, content } = slide.duplicate()

const newSlideId = context.uuid.new()

const newSlide = new Slide({ slideId: newSlideId, deckId, notes, content })

await context.slidesRepository.save(newSlide)

const { position } = slidesOrdering.insertSlide(newSlideId, slidesOrdering.getPositionAfter(slideId))

await context.slidesOrderingRepository.save(slidesOrdering)

return { newSlideId, position }

}

duplicateSlide command coordinates the work between two models - Slide and SlidesOrdering - to fulfill the use case.

Based on our past experiences, that operation is a bit tricky, as it spans multiple models, which might make concurrent state changes a bit challenging.

Saving a new slide might succeed, but saving the updated slides ordering might fail due to optimistic concurrency violation.

This is something that we could consult with Tom and his crew - what are the consequences of restoring the slides ordering, let's say in 30 seconds?

Or what would happen if the slides ordering is restored, but after 2 minutes?

We definitely should ask Tom about his workflow and tolerance for such situations - maybe he could accept a slight delay, especially that there are multiple rounds of refining the presentation.

This would allow us, instead of pursuing immediate consistency, letting the system arrive at full consistency, eventually.

Either change the slides ordering firstly, showing some kind of "a skeleton slide" without any content, and later fill in the contents.

Or create the slide with its contents, but without position in the ordering, and later insert it in the correct place.

It is not our sole responsibility to decide on that - we should collaborate with Tom to find the best fit for his workflow.

But the most important aspect is that we would have options - having autonomous models (please remember that "autonomous" does not mean "isolated") allow us to explore different consistency strategies, depending on the needs.

We could also bet on immediate consistency, if Tom's workflow requires that, but then of course we would need to handle potential concurrency violations, e.g. with retries and hope that it would get resolved in a reasonable amout of attempts.

New type of content!

This is a true banger!

Finally, Tom is confident about the solution and started presenting his ideas to the world.

We're (Tom, actually) getting customers, and Tom is happy.

One day, Tom came back with a new idea.

Hi, I have a new idea!

Product is doing great, people love it!

What do you think about it?

And he immediately sketched a rough idea of how it could look like:

Well, it's just a content type, right?

It shouldn't be a big deal.

Hmmm, but what about those numbers in front of the labels, close to the arrows?

Should we ask Tom about it?

I have a brillant idea - we could squeeze even more value out of that new type of content!

The same workflow as I use for slides!

What do you think?

Strange, isn't it?

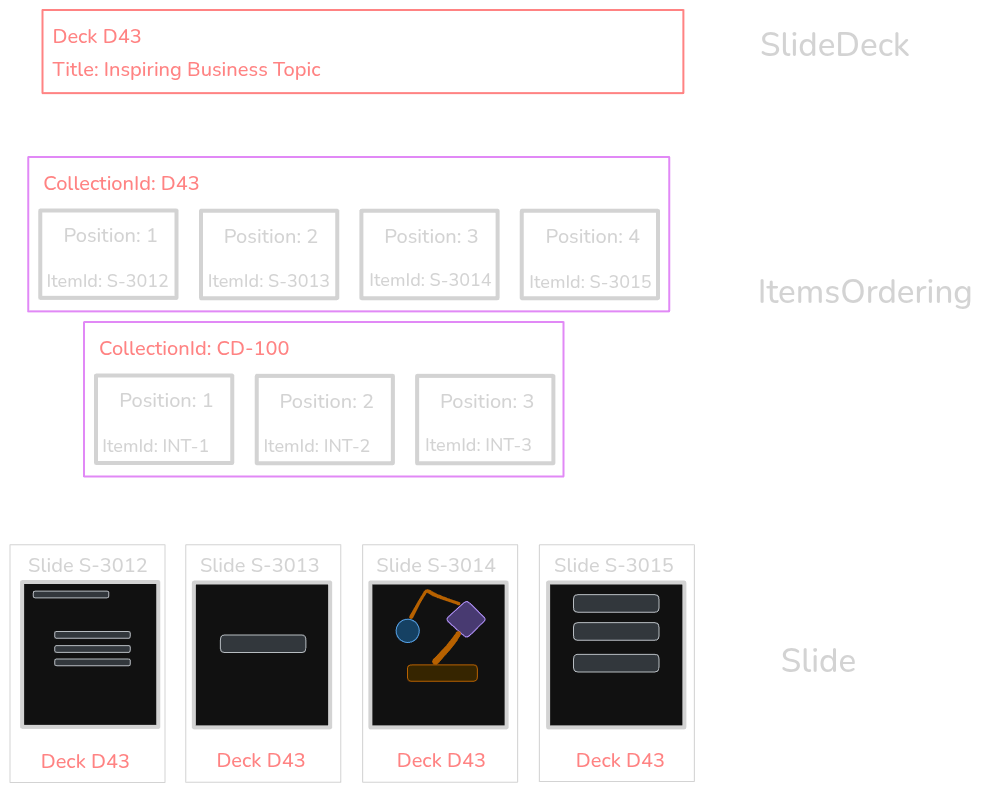

An avid reader might notice that reordering interactions within collaboration diagram is very similar to reordering slides within slide deck.

Do we really care what are we reordering?

We could easily say that in some contexts things are indistinguishable - we can reorder slides, interactions, people, widgets, books, pages, etc.

Such capability looks quite agnostic to slides so maybe we could distill even more reusable model?

And that is how ItemsOrdering model emerged:

class ItemsOrdering {

collectionId: CollectionId;

itemPositions: { itemId: ItemId, position: PositiveInt }[];

appendItem(itemId: ItemId): { position: PositiveInt } {

// ...

},

deleteItem(itemId: ItemId): void {

// ...

}

insertItem(itemId: ItemId, position: PositiveInt): void {

// ...

}

moveItem(itemId: ItemId, newPosition: PositiveInt): void {

// ...

}

moveItems(itemIds: ItemId[], newPosition: PositiveInt): void {

// ...

}

}

This model can be used in various use cases, including both slide decks and collaboration diagrams.

The knowledge is kept inside of the single boundary, and we can compose its capabilities in runtime, depending on the needs.

An avid reader might notice that this model - ItemsOrdering - is completely ignorant about what kind of items it is ordering.

There is no notion about slides - that is the responsibility of "someone else", to give meaning to those items.

It can be either duplicateSlide slide command we saw earlier, or maybe moveInteraction command for collaboration diagrams.

Such translation might happen, at runtime - ForLoadingSlidesOrdering required capability by duplicateSlide use case (application level), provided by, e.g. SlidesOrderingRepository, would do such translation.

class SlidesOrderingRepository implements ForLoadingSlidesOrdering, ForSavingSlidesOrdering {

// ...

async load(deckId: DeckId): Promise<SlidesOrdering> {

const itemsOrdering = await this.itemsOrderingStorage.load({ collectionId: CollectionId.of(deckId) })

return new SlidesOrdering({

deckId,

slidePositions: itemsOrdering.itemPositions.map(ip => ({ slideId: ip.itemId, position: ip.position }))

})

}

// ...

}

duplicateSlide command would remain unchanged, still coordinating the work between Slide and SlidesOrdering.

But the most important part is that we have options to pick from.

Where is the presentation?

"Ok Damian, but where is the presentation now? I only see slide deck, slides, slide ordering" - you might ask, dear Reader.

It is everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

Presentation that is visible in the screen (along with slides and their contents, speaker notes), ordered correctly, with title "Inspiring Business Topic - 2025 Edition" - everything is composed together, at runtime.

Of course, there might be other techniques to prepare such view model more efficiently, etc. but the main point is that it gets composed from multiple, autonomous models.

Many contexts contribute into "a concept" of presentation - each of them support a separate perspective of it.

Each context establishes a boundary, providing a set of capabilities, and encapsulating related knowledge (and language).

The most important aspect is that those contexts can coexist and evolve independently, without "stepping on each other's toes".

Of course, we've seen that there are some use cases that might span multiple contexts, but it is our decision to compose them on our terms, not how models dictate so.

Throughout the whole tale, we were able to observe how compile-time composition (compile-time hierarchies) gave us struggles and challenges, especially when it comes to problems related to concurrent/competetive/collaborative problems.

We used all the occurring problems as diagnostic signals - feedback - and we were able to rethink our models, reorganizing responsibilities, distilling new models, until we reached satisfying level of autonomy (which does not mean isolation).

In a way, we moved from the domain model into a set of models that can be composed at runtime.

Each of "the components" (a perspective, a context) of a presentation: "slide deck" (providing title), "slides" (providing contents and notes) and "items ordering" (providing proper sequencing of slides) - are autonomous enough to allow concurrent modifications and independent evolution.

Whenever there will be another capability required, we should evaluate whether it fits into existing contexts, or maybe we should distill a new one.

ItemsOrdering - pure fabrication?

GRASP defines a concept of a pure fabrication:

A pure fabrication is a class that does not represent a concept in the problem domain, specially made up to achieve low coupling, high cohesion, and the reuse potential thereof derived (when a solution presented by the information expert pattern does not).

So in a way, Tom has never mentioned anything about "items ordering", at least explicitly.

Initially, we started with "slides ordering", but when we hit another variation of the same problem - it turned out that both use cases required a common capability.

By observing SlidesOrdering and potential InteractionsOrdering (for collaboration diagrams), we noticed that neither of them were "true" abstractions - they "abstracted away" only parts of the details.

When we started asking different questions, we were able to spot that in certain contexts it does not really matter what is being ordered - this actually allowed us to distill ItemsOrdering model, which abstracted the details even more, completely changing the level on which one operates.

"But we already had it - SlideDeck!" - someone might say.

Well, yes and no.

SlideDeck composed multiple perspectives in compile-time - which made concurrent workflows challenging.

Additionally, SlideDeck encapsulated too much knowledge, making it less cohesive, which directly contributed to the knowledge gravity problem.

Naming is framing - the name, SlideDeck, would frame one's thinking so that whenever there will be a need, one would try to fit the new requirements into existing model, rather than exploring new possibilities.

SlideDeck would grow, grow and grow, and become even bigger compile-time hierarchy, attracting more knowledge.

So moving "ordering capability" into a separate boundary, encapsulating knowledge (rules, information required to make decisions) explicitly, allowed us to isolate that "component".

In fact, everything boiled down to a certain way of organizing responsibilities to achieve desired qualities and goals.

As you saw, dear Reader, we were able to walk through different designs, exploring various options (and related trade-offs), knowing that each of the models might bring a certain cost of modelling.

The abstractions (perspectives) we've found, opened possibilities to move from concepts to architecture.

From compile-time hierarchies to runtime composition

Phew, that was a hell of a journey, wasn't it?

We started with a single model - SlideDeck - encapsulating all the knowledge about slide decks, slides, their contents, notes, ordering, etc.

We initially tried to model "the absolute" concept of presentation, that we could visualize on the screen.

Slowly but steadily, we visited various options and arrived at the point where we have many contextual models in our inventry so that we can compose them as we want.

I know that we faced a toy example and of course you, dear Reader, might be dealing with much more complicated and sophisticated domains - a simple slide deck might be "too easy".

Simplicity often mean making more things, not fewer

Nevertheless, it's all about the way of thinking - whether we try to see beyond compile-time hierarchies and embrace runtime composition of autonomous models.

Next time, when you face a problem that seems to be solvable,e.g. only on the infrastructure level, ask yourself, dear Reader:

Is there an abstract idea that I might need to represent explicitly?