- Published on

COCOA: from Ports & Adapters to concepts, capabilities and providers

- Authors

- Name

- Damian Płaza

- @raimeyuu

Time for a little (de)tour?

Imagine that we observe a discussion between a senior software engineer Dan, an architect Alex and a business stakeholder Pete.

Pete is working in local, guided tourism business and he tries to explain to Dan and Alex how a particular workflow is working, so that they can modernize the technical side of it (because technical people should bother only by technical matters, right dear Reader?).

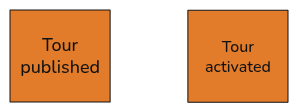

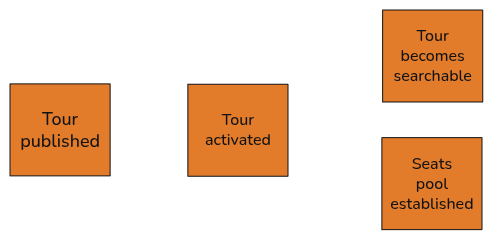

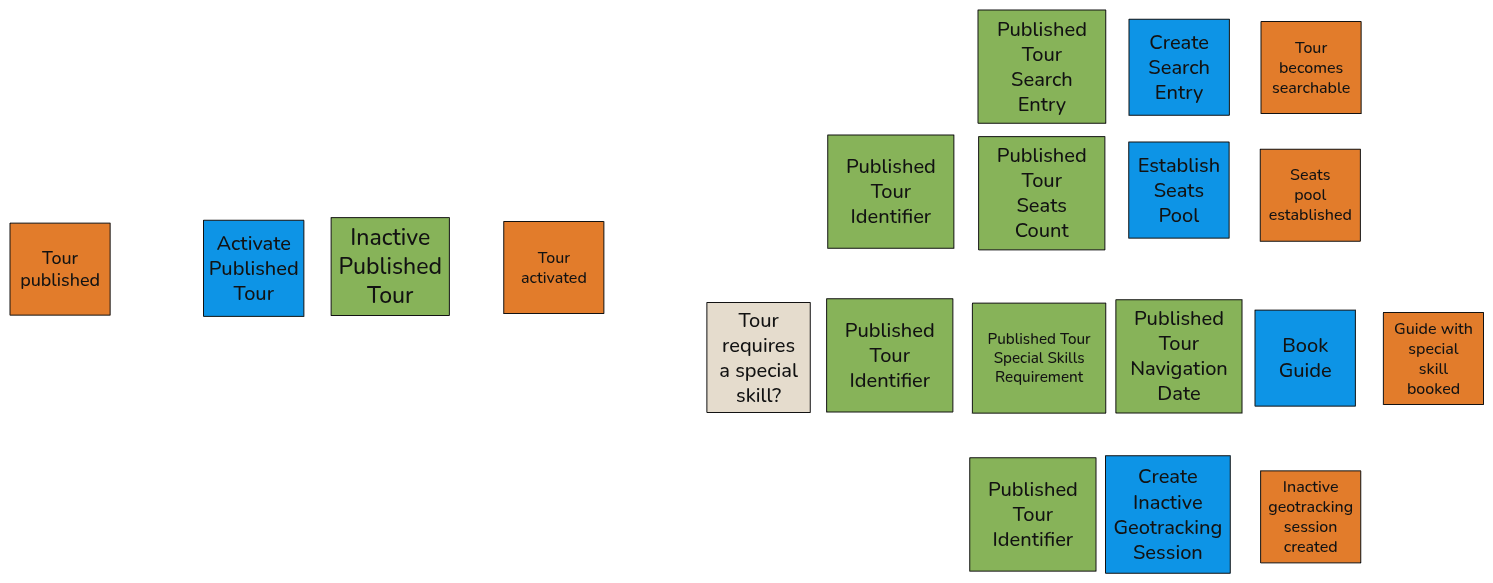

He explains the moment when a tour was published and what happens next.

So they pulled couple of stickies and following Event Storming notation, they created following visualization of the workflow:

Technical folks continued asking.

Pete visibly started thinking, while staring at the board, and then he continued explaining.

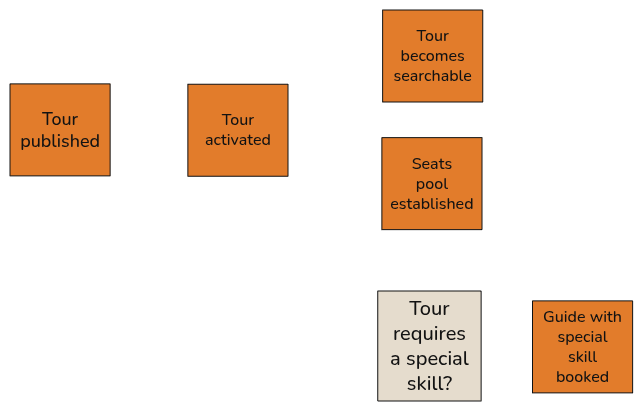

Alex was not happy that suddenly they jumped out of the topic of losing the location of participants, his architectural spider senses told him that something important is hidden there.

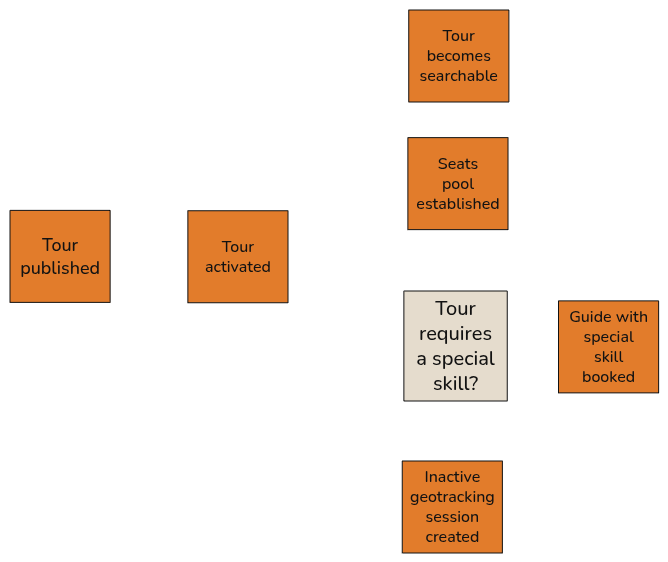

Dan walked to the board and placed another orange sticky, representing another consequence of activating a published tour.

Pete did not understand it in the first place, but both Dan and Alex explained the idea behind geotracking session and why it starts as inactive.

After couple of minutes of discussion, Pete nodded and confirmed that it matches his understanding.

They told him that as soon as the tour navigation starts, such geotracking session becomes activated, and guides will be able to track participants' locations.

Technical folks thanked the business stakeholder for his time and insights, and they went back to their office to started collaborating on the solution, using the insights and findings.

What is possible?

Alex looked at the board again, and he started thinking and mumbling to himself, at the same time.

Dan was typing something on the keyboard, and suddenly he stopped and looked at Alex.

Published Tour Activated. Then four services need to listen on it, translate it to a respective command, and handle those.Searching business capability, why do you want it to listen to a very specific event? It would creating coupling.And Dan started typing, representing his understanding of how to implement the published tour activation workflow.

public class ActivatePublishedTourCommandHandler(

IPublishedTourRepository publishedTourRepository,

ISearchService searchService,

ISeatsPoolService seatsPoolService,

IGuideBookingService guideBookingService,

IGeotrackingService geotrackingService,

IEventsPublisher eventsPublisher

)

{

public Task Handle(ActivatePublishedTourCommand command)

{

var publishedTour = await publishedTourRepository.Load(command.PublishedTourId);

if (publishedTour is null)

{

throw new PublishedTourNotFoundException(command.PublishedTourId);

}

publishedTour.Activate();

await publishedTourRepository.Save(publishedTour);

await eventsPublisher.Publish(new PublishedTourActivatedEvent(publishedTour.Id));

await searchService.CreateSearchEntry(@for: publishedTour.ToSearchEntry());

await seatsPoolService.EstablishSeatsPool(publishedTour.Id, publishedTour.SeatsCount);

if(publishedTour.RequiresGuideBooking)

{

await guideBookingService.BookGuide(publishedTour.Id, publishedTour.RequiredGuideSkills, publishedTour.NavigationDate);

}

await geotrackingService.CreateInactiveGeotrackingSession(publishedTour.Id);

}

}

Even though Dan was very keen on going fully with Event-Driven Architecture, because he believed in its benefits, he decided to implement the entire workflow in a single command handler.

It reflected exactly what was visualized on the board, and it was easy to understand.

And because it was easy to understand, it was easy to debug, test, and maintain.

Alex looked at the code, and asked about what happens if one of the services fails - whether the entire operation is expected to be rolled back, or not.

But the discussion quickly stopped and both of them started doing circles between business capabilities and ports and adapters.

Clean, adaptive hexagonal ports, or something else?

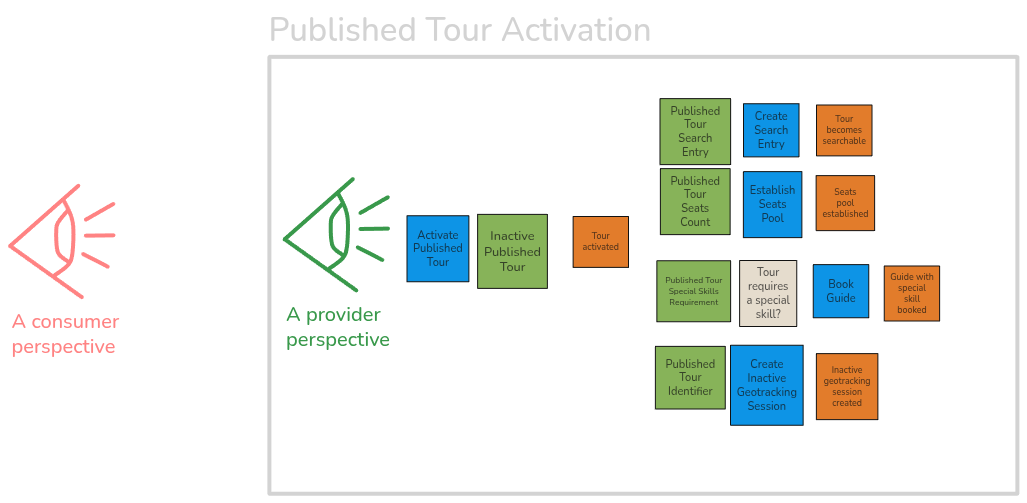

They included blue stickies for commands and green stickies representing state that is used in a particular step of a workflow.

Now the board reflected the code better, and both Dan and Alex were happy.

Alex was curious about the mismatch between the language that he used and what Dan used.

Dan pointed to the command handler constructor parameters, and Alex nodded.

Then, he showed all the interfaces representing those ports:

public interface IPublishedTourRepository

{

Task<PulishedTour?> Load(PublishedTourId id);

Task Save(PublishedTour publishedTour);

}

public interface ISearchService

{

Task CreateSearchEntry(SearchEntry entry);

}

public interface ISeatsPoolService

{

Task EstablishSeatsPool(

PublishedTourId publishedTourId,

int seatsCount

);

}

public interface IGuideBookingService

{

Task BookGuide(

PublishedTourId publishedTourId,

IEnumerable<Skill> requiredSkills,

DateTime navigationDate

);

}

public interface IGeotrackingService

{

Task CreateInactiveGeotrackingSession(PublishedTourId publishedTourId);

}

public interface IEventsPublisher

{

Task Publish(DomainEvent domainEvent);

}

EstablishSeatsPool is implemented?Dan felt that something important just clicked in his mind.

Ports were not just technical abstractions, they could be expressions of business capabilities, that are required by a particular use case!

He was wondering about the implications of that realization, so he immediately asked about adapters.

Dan was enlightened.

This means that ports and adapters can express something more profound than just another way of structuring software.

Then can be used to express business capabilities and their providers.

And what truly matters is a perspective - a command handler can be either a capability provider or a consumer, requiring other capabilities.

But never both at the same time, as holding two perspectives is really difficult, if not impossible.

Alex asked Dan to show him a directory structure of the project, so that they can see how those concepts are expressed there.

src/

└── ActivatePublishedTour/

├── Adapters/

├── Api/

├── Domain/

├── Ports/

└── ActivatePublishedTourCommandHandler.cs

Just to reinforce the idea of business capabilities, Alex asked if it matters, from a consumer, outside-in perspective, whether there is no folder structure inside ActivatePublishedTour/ folder, and Dan agreed that it does not matter.

"I think that's what is advocated through Vertical Slices", he thought to himself.

After expanding all the directories, they saw following structure:

src/

└── ActivatePublishedTour/

├── Adapters/

│ ├── PostgresPublishedTourRepository.cs

│ ├── RabbitMqGuideBookingService.cs

│ ├── RabbitMqGeotrackingService.cs

│ ├── RabbitMqSearchService.cs

│ └── RabbitMqSeatsPoolService.cs

├── Api/

│ └── Http/

│ └── ActivatePublishedTourEndpoint.cs

├── Domain/

│ ├── Events/

│ │ └── PublishedTourActivated.cs

│ └── Models/

│ ├── PublishedTour.cs

│ ├── SearchEntry.cs

│ └── Skill.cs

├── Ports/

│ ├── IEventsPublisher.cs

│ ├── IGeotrackingService.cs

│ ├── IGuideBookingService.cs

│ ├── IPublishedTourRepository.cs

│ ├── ISearchService.cs

│ └── ISeatsPoolService.cs

└── ActivatePublishedTourCommandHandler.cs

Alex smiled and asked, knowing what they both learned, if they could do a little renaming.

The idea was to rename Ports/ directory to RequiredCapabilities/, Adapters/ directory to Providers/.

Additionally, rename Domain/ to Concepts/, which made Dan a little bit confused, as they were not discussing that before, but Alex asked to firstly do so and then they could discuss it.

src/

└── ActivatePublishedTour/

├── Api/

│ └── Http/

│ └── ActivatePublishedTourEndpoint.cs

├── Concepts/

│ ├── Events/

│ │ └── PublishedTourActivated.cs

│ └── Models/

│ ├── PublishedTour.cs

│ ├── SearchEntry.cs

│ └── Skill.cs

├── Providers/

│ ├── PostgresPublishedTourRepository.cs

│ ├── RabbitMqGuideBookingService.cs

│ ├── RabbitMqGeotrackingService.cs

│ ├── RabbitMqSearchService.cs

│ └── RabbitMqSeatsPoolService.cs

├── RequiredCapabilities/

│ ├── IEventsPublisher.cs

│ ├── IGeotrackingService.cs

│ ├── IGuideBookingService.cs

│ ├── IPublishedTourRepository.cs

│ ├── ISearchService.cs

│ └── ISeatsPoolService.cs

└── ActivatePublishedTourCommandHandler.cs

Dan was excited about the new terminology. It seemed to him that while talking to business stakeholders, it was easier to talk about "capabilities" rather than "ports" or "commands".

Also, "providers" sounded slighlty more humane than "adapters".

It almost felt as super powers - was that the secret technique used by enterprise architects to communicate with business stakeholders?

Finally, "concepts" made perfect sense - it expressed the idea of focusing on what matters in a specific context.

He was eager to try those new terms in his next conversations with business stakeholders.

Hexagonal? Clean? Onion? Hardware?

Ok, time to stop this lovely tale.

"You must be kidding me", some Readers could think right now.

"It's soo foolish to rename well-known terms like ports and adapters to capabilities and providers, and domain to concepts!", others might comment in their heads.

"You did so just to sound fancy and different!", one could accuse.

"Isn't it a SOA reincarnation?", yat another could blame.

How dare I propose a new terminology, in the world where so many architectural patterns already exist, describing similar ideas?

Whatever we mentally do, as human beings, we build mental models.

A model is like a metaphor - it's not created to be perfect, accurate, and complete.

It is brought to life to help us understand something, to reason about it, to communicate our understanding to others.

It might have its flaws, but if it emphasizes the essentials, it does its job.

Isn't abstractions just that - imperfect mental models that help us reason about complex things?

Nevermind, let's get back to the point.

We use a variety of models to describe application architecture: hexagonal architecture, onion architecture, clean architecture, ports and adapters architecture.

Some of them were named after the shape, some were named after "clean code" to sound similar, others were named after hardware and the idea separating ports from adapters.

Each of them convey profound ideas that shape the way we reason about our applications, and aim at bringing certain qualities.

The big idea behind each of them is to isolate the application logic from the outside, external concerns, to make everything testable and maintainable.

But nothing really stops us from using THE domain model, a single entity for everything.

It will attract more and more the knowledge, growing into enormous size, becoming unmaintanable, untestable, and inflexible.

To counteract that, CQRS-thinking comes into play, helping us with model segregation: some for writing (or making a decisions), others for reading (or presenting information to make a decision).

Commands typically need little information, just to make a decision with transactional integrity, whereas queries might require tons of information, aggregated from various sources, to present a complete picture.

And nothing really stops us from coupling decision models across various use cases, making them interdependent and inflexible.

To counteract that, Vertical Slices-thinking comes into play, helping us with reasoning about independent use cases, where isolation and possible duplication are acceptable for independent evolution.

Of course, we're touching only the surface of these topics.

All of those models are imperfect, but useful - they help us reasoning and communicating about complex things.

When one developer says "port", another one immediately understands what is meant.

In a way, those are the language patterns technical people use to communicate.

What about communicating across boundaries?

When we communicate with business stakeholders, would they understand what is meant by "port" or "adapter"?

"Of course not, you dummy" - one might easily answer.

No one uses such words in business conversations, right?

How naive one would be to use entity, aggregate, repository or even domain in conversations with business stakeholders - those terms are pretty tactical, "low-level", and technical.

Others can use "use cases", "features", "services" - but those terms are so overloaded that they hardly help in communication.

Somehow architects are able to reason about business, enterprises, without stepping too much into technical details (which many times is a problem on its own, but let's leave it for another blogpost).

Through our tiny tale, we saw how an architect and a software engineer struggled to find a common ground to effectively communicate.

How often do we see that happening in real life - two technical folks discussing a solution, but failing to understand each other?

The idea behind this tale is not to resolve all the misunderstandings, and conflicts that arise in such conversations - oh no.

It is yet again an attempt to show that naming is framing - how we name things shapes the way we think about the world.

WHAT, not WHO and not HOW

Living next to Ports&Adapters and other types of application architecture might make us blind to strategic aspects of the business area we might build software solutions for.

And please do not get me wrong, dear Reader - I am not saying that Ports&Adapters and others are bad, incorrect, or that we should abandon it.

"All models are wrong (=imperfect, an interpretation of mine), but some are useful", as George Box said.

Let's start - what is a business capability?

What a business does or needs to be able to do to achieve its objectives.

A longer version:

An ability of an organization to perform a particular business activity, supporting its business operations and goals. It's a stable, abstract description of business functions that doesn't change much over time, regardless of how the organization is structured or which technologies are used.

Both are inspired by enterprise architecture thinking.

The most important is that we focus on WHAT needs to be done, not HOW and not WHO.

So we frame our thinking around capabilities - what needs to be provided to satisfy consumer needs.

Needs are very important as they enable the way of reasoning, Outside-In one, that drives everything.

Ideally, there should be one technical authority for a business capability.

In other words, one (capability) provider.

One could say that as long as the capability is provided with success, it does not matter who provides it, or how.

But when we step into a details of a given provider, suddenly how matters a lot.

Such provider becomes a consumer, requiring other capabilities in order to provide the capability it was contracted with.

A (capability) provider uses concepts that depict important ideas that matter for that capability.

Those abstract terms mean something inside that boundary, as if there were invisible contours outlining the context in which those concepts make sense.

Additionally, conceptual outlining helps counteracting absolute, universal and reality-chasing models that suffer from the knowledge gravity problem.

Yes, dear Reader, if you are familiar with Domain-Driven Design, you might see some similarities with Bounded Contexts and Ubiquitous Language.

And I think it might be quite important to express it explicitly, when we discuss application architecture.

Here comes the idea of COCOA - Capabilities-Oriented, Concepts-Outlined Architecture.

COCOA: Capabilities-Oriented, Concepts-Outlined Architecture

In COCOA, we would like to reason about application architecture through the lens of business capabilities, their providers, and concepts that outline the context in which make sense.

One shouldn't forget the big picture, the high-level persperctive, thinking only about low-level tactical details.

Sometimes a required capability would be provided by team-owned service, whereas other times it would be provided by a third-party system.

The capability does not change, but the provider does.

While testing, one might mock a required capability by using a mock provider so that we are able to verify if a specific step happened.

But when we register dependencies in the composition root, we would use a real provider that communicates with another system over HTTP, or a database.

Summing it all up:

- When we think about concepts, we think about WHAT abstract ideas and terms matter in a specific context.

- When we think about capabilities, we think about WHAT needs to be provided, not HOW and not WHO, from the persperctive of a consumer.

- When we think about providers, we think about WHO provides the capability, and HOW it is provided, but only from the perspective of that provider.

Capabilities are pretty important here, emphasizing the behavioral aspects of the system.

Reasoning behind that is similar to Sandi Metz's words about objects and messages:

You don't send messages because you have objects, you have objects because you send messages.

Which can be rephrased in the context of capabilities and providers as:

You don't have capabilities because you need providers, you have providers because you need capabilities.

And of course, now you might be thinking now, dear Reader, if we discussed "business capabilities", what about "business processes"?

Let's get a brief definition.

A business process is how the business does something.

And a longer version:

It's a specific sequence of activities, steps, and tasks that transform inputs into outputs. Processes are more concrete and can change frequently as the business optimizes operations or adopts new technologies.

Doesn't it sound similar to a workflow we saw our three amigos visualizing on the board?

It was a logical sequence of steps that needed to be performed to achieve a specific goal.

A description of HOW something is done.

In that context, the goal was activating a published tour.

Let's shift our focus to the problem of locating "lost participants", that Pete mentioned.

He described HOW a guide (WHO) tried to locate lost participants by calling them over the phone, asking repeatedly until they reached the group.

So the guide was a capability provider in that context.

The architect and the software engineer suggested an abstraction - "geotracking" capability.

They tried to depict WHAT needed to be provided.

Of course, when this "geotracking" capability is provided by a software system, there will be a sequence of logical steps to provide it.

But yet again, it is a matter of the perspective.

When we look from outside, as consumers, we care about WHAT.

When we look from inside, as capability providers, we care about HOW.

For a consumer - it does not matter HOW geotracking is provided, as long as it is provided.

For a provider - it matters HOW geotracking is provided, as long as it satisfies consumer needs.

If we are outside the boundary, reasoning will be framed around capabilities.

If we are inside the boundary, reasoning will be framed around processes.

Why COCOA?

You might be wondering, dear Reader, why and how on earth I came up with COCOA.

It's because I love chocolate?

Am I a cocoa farmer on the side?

I needed a catchy phrase, that's all.

The big thing is not the name, not the symbol, not the abstraction.

The real deal is the mental model behind it.

I tried to reflect on my experiences and observations, and synthesize them into something useful.

A mental model that mainly helps me with reasoning and helps me with communication.

It enables me changing the levels (using Gregor Hohpe's The Software Architect Elevator metaphor), connecting higher-level, strategic thinking with tactical, technical implementations.

As mentioned before, I am not saying that Ports & Adapters (and others), CQRS and Vertical Slices are anyhow "bad" or "incorrect".

I learned from them, used them, drew from them, and they shaped the way I think about application architecture.

COCOA is another model one can use to think about application architecture.

It still uses isolation, separation of concerns, and other qualities, but it also tries to capture and emphasize strategic aspects of the business area we are building software solutions for.

Organizing code is very important topic to many, so how potentially COCOA would look like in practice?

src/

└── ActivatePublishedTour/

├── Api/

├── Concepts/

├── Providers/

├── RequiredCapabilities/

└── ActivatePublishedTourCommandHandler.cs

And when expanding all the directories:

src/

└── ActivatePublishedTour/

├── Api/

│ └── Http/

│ └── ActivatePublishedTourEndpoint.cs

├── Concepts/

│ ├── Events/

│ │ └── PublishedTourActivated.cs

│ └── Models/

│ ├── PublishedTour.cs

│ ├── SearchEntry.cs

│ └── Skill.cs

├── Providers/

│ ├── PostgresPublishedTourRepository.cs

│ ├── RabbitMqGuideBookingService.cs

│ ├── RabbitMqGeotrackingService.cs

│ ├── RabbitMqSearchService.cs

│ └── RabbitMqSeatsPoolService.cs

├── RequiredCapabilities/

│ ├── IEventsPublisher.cs

│ ├── IGeotrackingService.cs

│ ├── IGuideBookingService.cs

│ ├── IPublishedTourRepository.cs

│ ├── ISearchService.cs

│ └── ISeatsPoolService.cs

└── ActivatePublishedTourCommandHandler.cs

So nothing really changed, one could comment.

"It's just a naming, fool", some might say.

But naming is framing, when we see "geotracking" required capability, might it be that another team requires it also?

Might it be that we can reuse that capability in other contexts?

If not, what can we do to make it reusable?

If yes, why aren't we doing it?

I am not saying about reusing that interface, but reusing the capability.

Aligning the language used, possible web services providing that capability, and so on.

"You say providers - how does it differ from services?", one might ask.

Well, as many concepts in our industry, "service" is an overloaded term.

Appearing on different levels of abstractions - an application level, an architecture level, a business level.

Many might hold an image of services having dozens of methods, exposing too big API surface, making them impossible to change.

I hope you know, dear Reader, I am more interested in roles things play.

And I am not the first one who tries to express an important role something plays by renaming it.

In COCOA, capabilities strive to emphasize the contextual behaviors.

Concepts aim at expressing contextual models.

Finally, providers embody "the doers", but they shall come last in the whole process.

I only give it a name so that I can refer to it later.

It is a useful abstraction, a mental model, still being imperfect.

I don't aim at building a school or a church around it - it's goal is to help different reasoning.

Should you use COCOA?

When you get back to work, refactor all codebases, align with COCOA.

And give me fifty.

Ok, jokes aside.

I don't know, dear Reader.

You might find it useful, or not.

COCOA doesn't throw away isolating application logic from outside concerns, used to achieve testability, which is advocated by Ports & Adapters and others.

COCOA doesn't throw away locality of behavior, used to achieve high cohesion and evolvability, which is advocated by Vertical Slices.

COCOA doesn't throw away segregation of models, used to achieve maintainability and flexibility, which is advocated by CQRS.

COCOA doesn't throw away domain modeling, used to achieve alignment with business areas, which is advocated by Domain-Driven Design.

All of those abstract ideas need to live in the designer's mind.

COCOA is a way of reasoning, nothing more, nothing less.

Expressing COCOA through code organization is just a way to express those ideas.

You can have a single file, having all of mentioned ideas, and COCOA will be there.

You can have a complex directory structure, and COCOA will appear again.

COCOA is in the eye of the beholder, same as a tree that falls in the forest, and no one is around to hear it.

Remember: systems are built by, with and for people.

Talk to your experts, collaborate with people - that's what truly matters.

Happy building!